On Sunday, 11 Jan, 2026, a peaceful Nagar Kirtan—a Sikh religious procession symbolizing community unity and spiritual devotion—was disrupted by hostile protesters in Tauranga, New Zealand, causing shock and concern among Sikhs worldwide. This incident is one among several troubling episodes in recent times where Sikhs, and Indians broadly, have been subject to hate crimes or racial discrimination away from home.

According to United Sikhs, an international non-profit humanitarian organization, in the United States alone, Sikh Americans were the third most frequently targeted religious group in the latest FBI hate-crime data, with 153 reported anti-Sikh incidents nationwide—including physical assaults, verbal abuse, and vandalism of Gurdwaras. In the UK, hate incidents have increased to such a point where events such as Turban Awareness Day were observed after a turban-wearing Sikh was attacked outside the Houses of Parliament. These are not mere statistics; they represent families living, working, and contributing to their communities—only to face misunderstanding and prejudice.

This targeting stands in stark contrast to the culture of assimilation and communal harmony that India embodies. Across Indian cities—from Amritsar to Delhi, Ludhiana to Jalandhar—Sikh festivals such as Gurpurab and Nagar Kirtans are celebrated not only by Sikhs but members of other faiths too. Langar (community kitchen) is shared freely; roads are adorned with lights and banners; and state administrations help facilitate public safety and participation. This is the Indian way of integrating diversity into shared civic life—a model of pluralism and unity.

Sikhs from Punjab and other parts of India have long been valued contributors abroad. In Canada, where they form one of the largest Sikh populations globally, they have contributed to agricultural success, small businesses, and civic life. Yet their achievements are unable to shield them from xenophobia.

At the same time, it is vital to recognise that a small minority within the diaspora promotes separatist agendas like Khalistan. Their activism—often loud and disconnected from an average Sikh’s realities—has sometimes alienated host-country natives instead of building bridges. It is not surprising then that when tensions arise, such fringe movements get little support from local citizens and governments. Instead, the diaspora communities draw strength from their cultural ties to India and support peaceful coexistence.

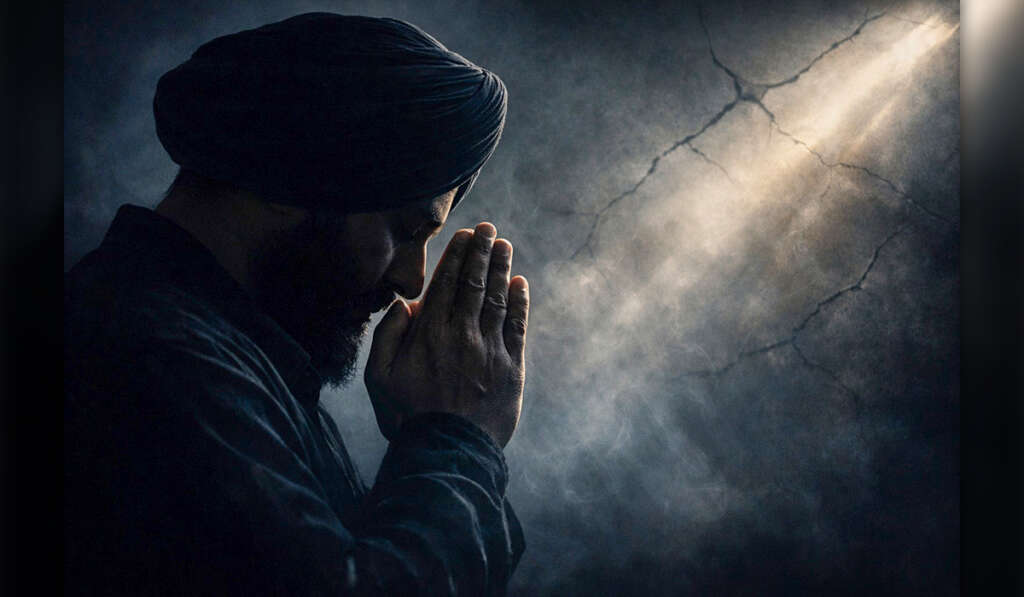

As Guru Nanak Dev Ji taught, “Na koi bairi, nahi begana, sagal sang ham ko ban aayi”—there is no enemy, no stranger; I am at peace with all. This principle lies at the very heart of Sikhism and it is a principle that has found its most natural expression in India’s plural, assimilative culture. For the global Punjabi and Sikh diaspora, India remains not just a place of origin, but a civilisational anchor—where Sikh identity is respected and celebrated, and is woven into the national fabric. When challenges arise abroad, it is this enduring bond with India that offers moral strength, cultural confidence, and diplomatic support. Punjab has consistently shown that pride in identity and respect for diversity can coexist; carrying that spirit globally is the strongest response to hate, and the most powerful message the Sikh diaspora can send to the world.

Leave a Comment