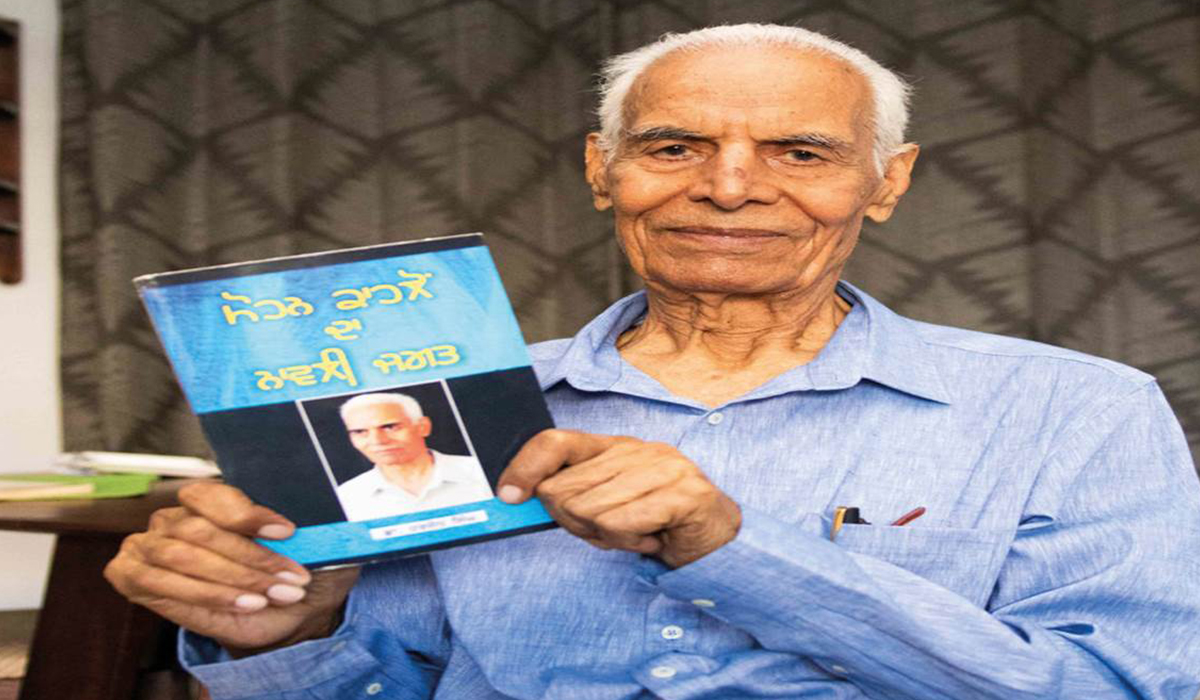

Mohan Kahlon was a keeper of the sorrows of the eastern bank of the Ravi. His village, Chhanni Teka, stood right on the far bank of the river. It was a village known for giving birth to fierce sons and strong-willed daughters. Mohan Kahlon was born there on November 11, 1932.

When he grew up, the country was partitioned in 1947. Chhanni Teka fell in Shakargarh tehsil of Gurdaspur district, across the Ravi. Once the river became the border, the village was left on the other side. Fourteen- or fifteen-year-old Mohan crossed over with his parents and settled in Kot Santokh Rai near Dhariwal.

Whenever he narrated the story of Partition, his voice trembled. Those were terrifying days. The village of Chhanni Teka had two sections divided by a high mud wall. Clashes between the people of the ‘Lehndi’ and ‘Chardi’ sides were frequent. Life on the riverbank was never easy. Mohan Kahlon’s father, Sardar Dharam Singh, took contracts for ferrying boats across the river and transported passengers daily. But when his own time came to cross, Muslim brothers from the village ferried them across in their boats. Kahlon would say that Punjab seemed possessed by a death-frenzy at the time. His mother, Dato, was pregnant at the time. Amid showers of bullets, the family crossed into Indian Gurdaspur. They possessed only one weapon — a spear.

The family owned some mortgaged land in Fattaywali between Ramdas and Majitha. It had been leased out, and survival was difficult. They bought some land and tried farming, but success did not come easily. Mohan was sent to his maternal village, Kot Karam Chand, where he passed eighth grade. He later joined Khalsa High School, Batala, then Sikh National College, Qadian. Due to his association with communist ideology and a speech he delivered, he was expelled with a written note that he should not be admitted to any other college.

During this period, Mohan Kahlon became a full-time worker of the Communist Party of India. Selling the newspaper Nava Zamana at Batala bus stand was his main responsibility. He met Dr. Harsharan Singh Dhillon of Ekalghadda. His maternal cousin Pyara Singh Randhawa was also progressive-minded. Through Dr. Harsharan, he met Deep Mohini, daughter of Pyara Singh Randhawa, who studied at Preet Nagar Activity School; the acquaintance later turned into marriage. Randhawa himself was a writer and worked in a refugee camp in Jalandhar, often narrating Partition stories at home. Many events in Deep Mohini’s novel A Morning in the Mist were drawn from her father’s accounts.

This background is essential because understanding a creator’s background is often more important than the creation itself. In exchange for land left in Chhanni Teka, the family received land in Bakhtpur, Chhota Chaura, and Fattaywali. Eventually they settled in Kot Santokh Rai near Dhariwal. His younger brother Sohan Singh Kahlon lived there; another brother, Gurnam Singh, settled in Jalandhar.

Mohan Kahlon also worked underground for the Communist Party. During Comrade Harkishan Singh Surjeet’s election campaign in Nakodar constituency, Kahlon cut his hair to avoid police identification. During this time, he completed his B.A. privately, earned a B.T. from Khalsa College of Education, Amritsar, and became a school teacher in Majitha. He financed his education by tutoring children. From a bookseller behind Hall Bazaar gate in Amritsar, he acquired world literature and studied deeply.

He befriended professors Dr. Gurnam Singh Rahi, Dr. Gurkirpal Singh Sekhon, and Dr. Harish Puri, which strengthened his ideological maturity. He completed his M.A. in Punjabi privately. By then, his poems were appearing in literary magazines. His friendship with Shiv Kumar Batalvi made him realize how far the true home of poetry lay. He turned to fiction and published his first story collection Raavi de Pattann. He then began writing novels.

His first novel Machhli Ik Dariya Di was written in 1967. Shiv Kumar Batalvi wrote its preface in poetic form under the title “Testimony”:

Until yesterday, I myself was his witness,

From today, this song of mine is witness.

Of deep pain and dense silence,

He is a river flowing in fullness.

During the creation of Shiv Kumar’s immortal work Loona, the two often traveled together to Batala, Amarnath, Baijnath. Some even claim Mohan Kahlon wrote the intense preface to Loona. Whenever asked, he would simply smile and say nothing.

His second novel Beri te Bareta (1970) created a stir across Punjabi literary circles. Pardesi Rukh (1972), Gori Nadi da Geet (1975), Barandari di Rani (1976), Kaali Mitti (1986), and Vah Gaye Pani (2003) followed.

When Gori Nadi da Geet, based on Shiv Kumar Batalvi’s life, appeared in 1975, readers responded warmly, but critics and family members accused it of mud-slinging. A toxic atmosphere surrounded him. He withdrew from public life. Rumours spread that he had died somewhere. Nearly twenty-eight years of self-exile followed. He went from home to school and back.

After retirement as a lecturer, he taught in Dinanagar and later at the In-Service Institute in Jalandhar. His only son, Rajpal Singh Kahlon, became the youngest lecturer at Guru Nanak Dev University. He later cleared the IPS (1981) and IAS (1984), receiving West Bengal cadre. Mohan Kahlon gradually settled in Kolkata, where National Library resources supported his writing. Nine years later, he published Vah Gaye Pani, about Punjabi soldiers in the First World War.

In 2003, Punjabi Sahit Akademi honoured him. Initially reluctant to return to Punjab, he was persuaded by Deep Mohini. He returned warmly and reconnected with friends. His storytelling was captivating.

His wife Deep Mohini passed away last year. Recently, though he recovered from COVID and returned from ICU, he suffered a heart attack. His son Rajpal says, “He wanted to live fully. He stayed connected with Punjab. He used to say he had just begun to enjoy his work, and now the race was ending. He would have turned ninety in November.”

Mohan Kahlon’s passing feels like the sunset of a unique style in Punjabi fiction. At his departure, one recalls Prof. Mohan Singh’s couplet:

The fragrance that blossomed in the flower’s heart has flown away.

Only then did the flower realize the weight of its own colors.

Leave a Comment