When all hopes of meeting Ranjha collapse, a deeper pain begins to seep into Heer’s heart — the realisation that after searching endlessly she may have found God, but not Ranjha, because even God is not like Ranjha:

I went searching for Ranjha, but I did not find him.

I found God, yet Ranjha remained lost — for God is not like Ranjha.

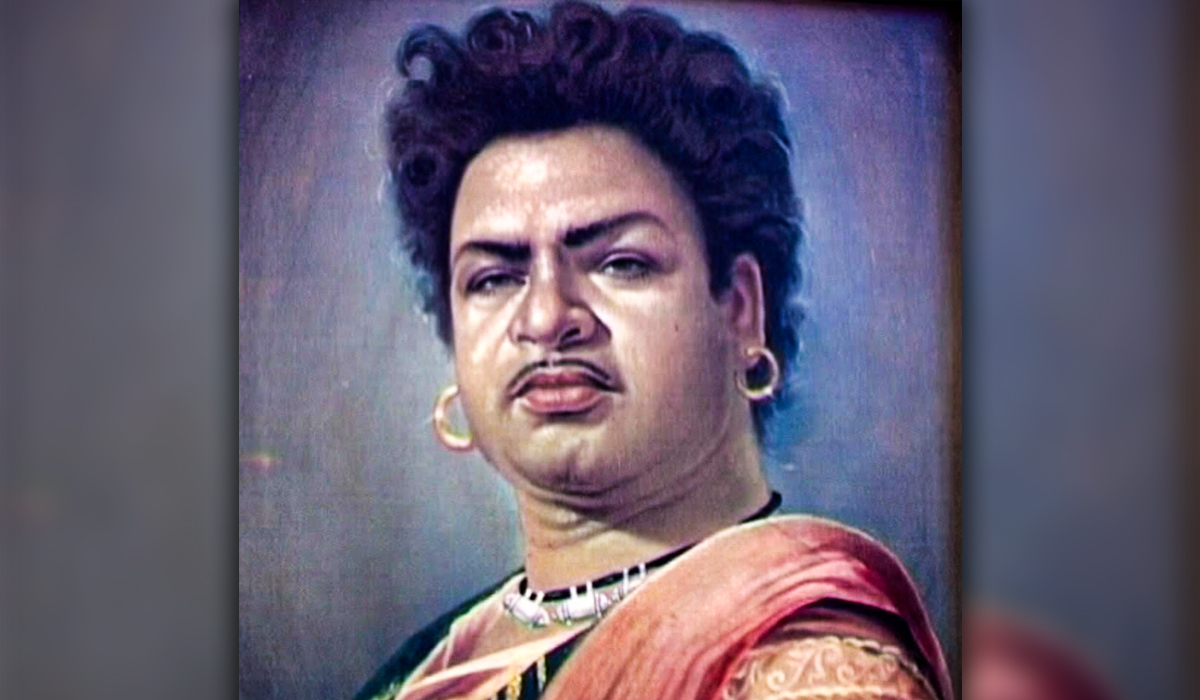

It was around 1992 when I somehow came across two cassette tapes of this immortal love story that was born from the soil of Punjab. The performance lasted nearly an hour and a half. There was a master singer–narrator who recited the qissa in a voice marked by restraint and emotional distance, and at intervals sang as Heer herself. Listening to this Heer alone for the first time, the renowned Urdu writer Mumtaz Mufti felt as though a voiceless slave was moaning in anguish over her oppression and sorrow.

For the past thirty years, I have carefully preserved Tufail Niazi’s singing for my moments of solitude. When I am sad, I listen to him. When I am happy, I listen to him. Sometimes, I listen to him without any particular reason at all. Each time, a catharsis occurs; each time, something within me and within the world reveals itself in a new way.

Tufail was born in 1916 in a small village called Maderan in Punjab’s Jalandhar district, into a family traditionally associated with pakhawaj players. In the Sikh-majority village of Maderan, his was the only Muslim household.

The railway station for his village was Sham Chaurasi — a town regarded as the cradle of dhrupad, the very foundation of Hindustani classical music. His ancestors had long kept company with the great vocalists of Sham Chaurasi.

Even in childhood, Tufail understood that while rhythm gives music its body, melody is its soul. So he abandoned the family profession and learned to sing. At a very young age, he took up the sacred vocation of singing Gurbani, kirtan, and shabads at the Pehni Sahib Gurdwara near Amritsar. A few years later, his father took him to Gondwal, also in Amritsar district, where Tufail travelled from village to village singing for a cow-protection organisation. These simple songs urged people to care for and serve cows.

During the four years he spent doing this work, Tufail came into close contact with Pandit Nathuram of Batala, from whom he learned the intricacies of several ragas and bandishes. Gondwal also hosted a smaller version of the Harballabh fair, where leading classical vocalists from places like Jalandhar, Delhi, Saharanpur, and Agra would gather. Tufail formed connections with them. Practising dhrupad in cowsheds and immersed in classical music, he developed such a deep attachment that he eventually joined the Rasdhari tradition. The Rasdharis worshipped Ram and Krishna and possessed a vast treasury of folk music.

After spending two years with the Rasdharis, Tufail Niazi formally joined a nautanki troupe. From this popular storytelling form, he learned the art of blending melody with narration. Alongside singing, he also acted, playing roles ranging from Puran Bhagat to Punnu, and from Ranjha to Mahiwal in various dramas.

As his singing absorbed influences from so many diverse and colourful worlds, a distinct style began to emerge. He formed his own troupe and started performing at fairs and gatherings. Bookings became regular. Livelihood fell into place. For the first time in his life, he began to earn a respectable income — and then Partition happened.

As Faiz wrote:

The world has estranged me from your memory;

The sorrows of livelihood are more seductive than you.

After reaching Multan, music drifted to the margins of his life. The question of survival resurfaced. On top of that, the local language of Multan was not something he fully understood. His experience in Gondwal came to the rescue, and Tufail quietly began trading in milk products and also took up work as a confectioner.

Then, a few months later, like an angel in disguise, an old friend named Khushi Mohammad Chaudhry walked into Tufail’s shop. They had known each other since the Jalandhar days, and Chaudhry had joined the police department in that part of Multan. He recognised Tufail and scolded him affectionately for turning from a singer into a halwai. Khushi Mohammad Chaudhry got the shop vacated, arranged musical instruments, collected money from various sources, and helped Tufail return to music.

Even after mastering a craft, great success depends heavily on fortunate coincidences. Through such coincidences, Tufail one day found his way to radio, and then to television. After his first major television performance, Tufail Niazi captured the hearts of listeners. Even after his death in 1990, he is still counted among the greatest folk singers of the subcontinent.

After passing through so many winding paths and outwitting countless labyrinths of livelihood, when peace finally arrived in his life, he began worshipping pain — and for the rest of his life, he sang only Heer. What greater act of devotion could there be than giving voice to the pain of a Heer whose Ranjha was greater than God himself, and whose only possible union lay in their tragic deaths?

Listening to Tufail Niazi is like falling in love.

Leave a Comment