The entire phenomenon of Ataullah Khan is hidden inside a carefully manufactured story.

The cassette revolution that began in the mid-1980s carried music from across the world into India’s most remote villages and small towns. In that era, Madonna’s “Papa Don’t Preach” reached tiny Indian settlements just as easily as Mehdi Hassan’s “Pyar Bhare Do Sharmile Nain.” Around the same time, one cassette company pioneered a thriving business of imitation voices—fake Rafi and Kishore clones. Sold at nearly one-third the price of HMV and EMI, these cassettes pulled music out of elite drawing rooms and made it accessible to the masses.

By the 1990s, trucks and auto-rickshaws across India were fitted with tape recorders known as “decks.” This pairing of T-Series and the deck became the engine behind Ataullah Khan’s nationwide popularity.

Whether it was an auto crawling from ISBT to Mehrauli in Delhi’s heat, or a truck travelling the long stretch from Kanpur to Guwahati, drivers invariably carried one or two Ataullah Khan cassettes in their collections. Ataullah Khan gave voice to the incomplete love stories and unspoken sorrows of a community stripped of family life and personal intimacy. Through his voice, these people found the sound of their own longing.

Imagine a young, drowsy truck driver navigating highways at three in the morning, alert at every turn for police checks. Naturally, memories of his beloved surface. In that restless moment, he plays “I tried to forget you, but I couldn’t,” and for the next five to seven minutes, his soul transforms into something akin to a saint.

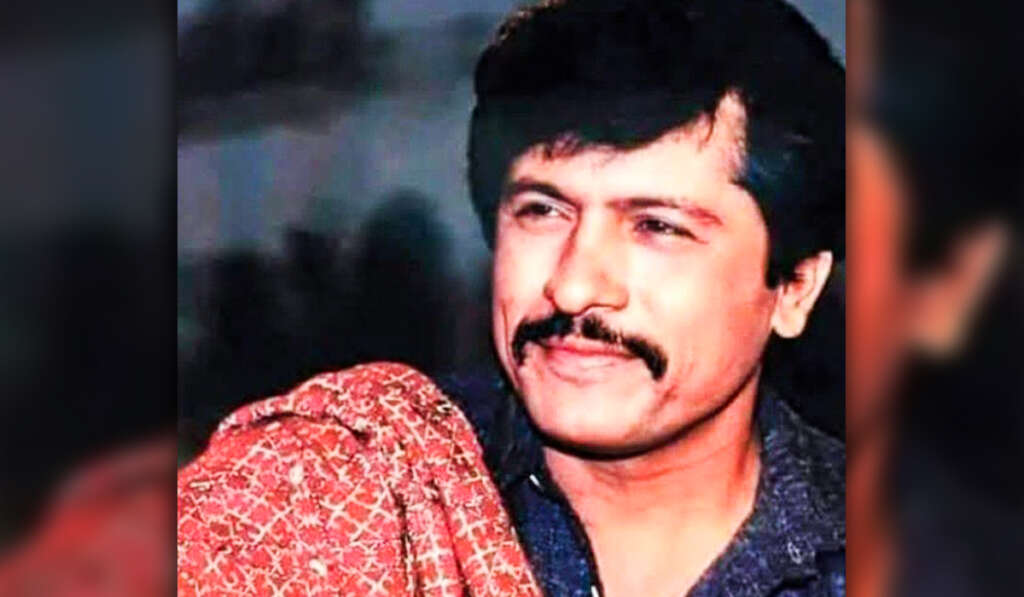

Born on 19 August 1951 in the small village of Isa Khel near Mianwali in Pakistan’s Punjab, Ataullah Khan Niazi became the subject of a fabricated tale crafted by some cunning mind and spread across India. It is unclear whether this story ever circulated in Pakistan.

According to this tale, Ataullah had a lover who betrayed him and chose to marry someone else. On the wedding day, Ataullah allegedly arrived at the ceremony and killed the groom. He was arrested, tried, and sentenced to death. All his songs, it was claimed, were written, sung, and recorded inside prison.

This overtly cinematic narrative appealed deeply to India’s wounded masses—people fed on shallow portrayals of love in Hindi cinema. It was even said that all of Ataullah’s recordings were made behind bars.

To further boost cassette sales, another rumour was floated: Ataullah must be freed, and enormous sums of money were required. Cassette companies were fully committed, hiring the world’s most expensive lawyers. A portion of every cassette sold would fund the legal battle. Fans eagerly joined this “holy cause,” sending money orders and bank drafts to cassette company offices. Beyond trucks and rickshaws, Ataullah’s slightly muffled yet profoundly deep voice began echoing in roadside eateries and small stalls, declaring:

“Your betrayal will kill me.”

For nearly a decade, Ataullah Khan applied a healing balm of love to North India’s poor and marginalised—an emotional language previously reserved for the middle class. That same middle class mocked his voice and repeatedly, unsuccessfully, tried to ignore him.

Then something happened, and Ataullah Khan vanished from public memory.

A decade ago, Coke Studio reintroduced him in a new form. Later, when he appeared again in the remix video of “Hum Dekhenge” alongside Faiz and Iqbal Bano in 2018, curiosity about him resurfaced among Indian audiences.

For those who have long dismissed Ataullah Khan as a crude singer, it is worth noting that since the early 1970s he has been regarded as a major figure in Punjabi, Pashto, and Siraiki folk music. His country honoured him with the Sitara-e-Imtiaz and the Pride of Performance awards. He commands a cult following, with countless admirers affectionately calling him Lala (elder brother).

Living in a classical haveli adorned with arches and intricate carvings, Ataullah Khan comes across in interviews as soft-spoken and exceptionally intelligent. Always dressed in a Pathan suit and shawl, this master folk singer has long been the uncrowned king of underground music.

The prison-and-gallows story is entirely false. The truth is that he married four times. This singer, who turned the wounds of love and betrayal into an extraordinarily successful enterprise, received so much love in life that one could envy him endlessly.

About the Author : Ashok Pandey is a renowned poet, painter, and translator. His first collection of poems, “Dekhta Hoon Sapne,” was published in 1992. His other well-received books include “Jitni Mitti Utna Sona,” “Tarikh Mein Aurat,” and “Babban Carbonate.” He blogs under the name Kabadikhana at kabaadkhaana.blogspot.com. He currently resides in Haldwani, Uttarakhand.

Leave a Comment